William Kentridge – Instructions on making sense of the world

William Kentridge, the master of creative cross-fertilisation, brings together worlds of performance and animation into galleries and stages worldwide.

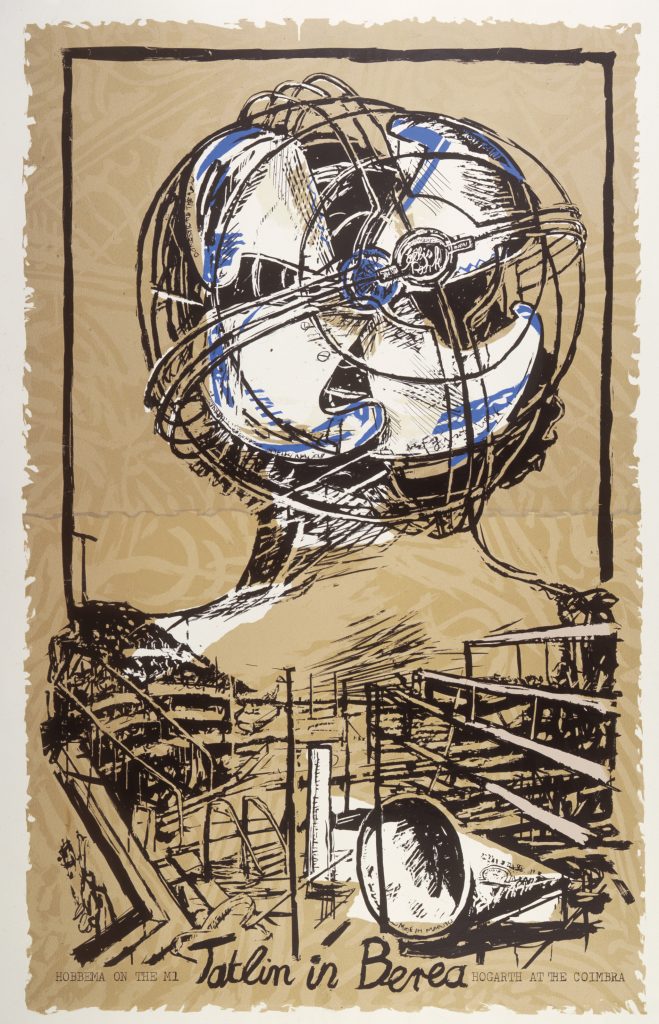

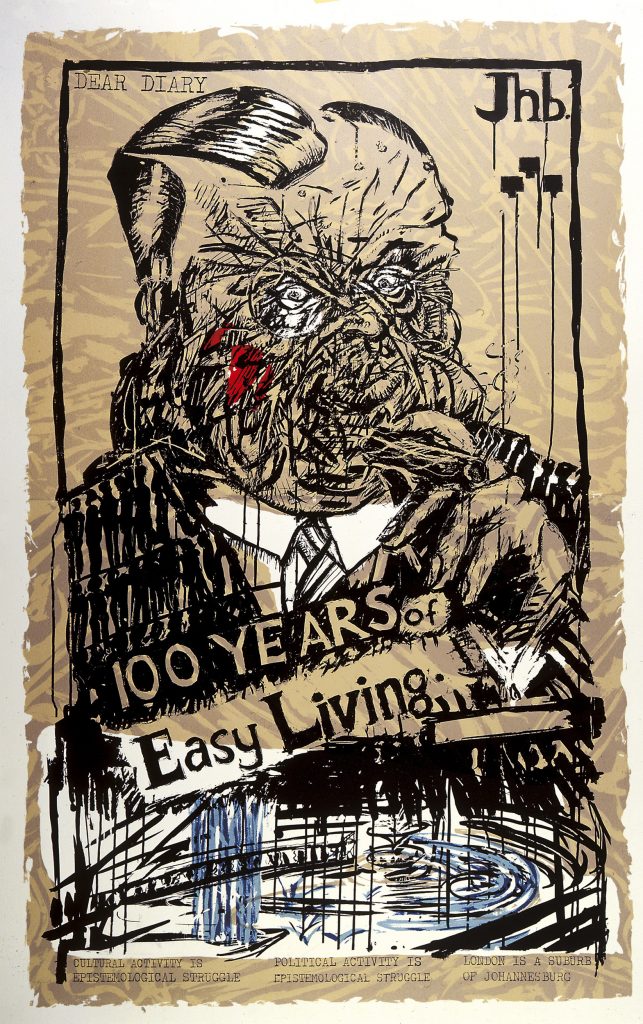

It’s a Tuesday evening at the Johannesburg studio of one of South Africa’s most acclaimed artists, William Kentridge. He is sitting at his drawing table with twelve silkscreened texts, part of a series of blue rubrics, shouting in capital letters “my red bicycle”, “enough and more than enough,” “struggle for a good heart,” “a box of shame,” “that which we do not remember”… With these chattering in the background, William Kentridge talks about his lifelong activity in the studio, trying to make sense of the world.

TLmag: What is your main focus in 2018?

William Kentridge (W.K.): My main project is, The Head and the Load, a performance piece looking at Africa in the First World War. While I look at Africans in Europe, my primary focus is the war itself in Africa. The Carrier War had an alternative story, where hundreds of thousands of porters carried the war on their heads. There were over a million casualties in Africa, from the first days after the declaration of war, until two weeks after the armistice. It’s a history unknown in Europe and was a history unknown to me until I started working on the project. The project is in response to my ignorance, as a goad and provocation to myself. The Head and the Load will exist as a performance piece at the Tate Modern, London, the Ruhrtriennale in Bochum, Germany and the Armory, New York. It will also travel to Amsterdam next year.

TLmag: You recently launched the ‘Centre for the Less Good Idea’ in Johannesburg. What is your concept of “the less good idea” and its importance to you as an artist?

W.K.: The centre is there to show artists and performers the pleasures of collaboration across disciplines; the energy gathered from different people working together, and the possibilities from working with someone outside of your medium. So the drawings a draughtsman will make can be provoked by working with a theatre person, rather than another artist and those results are something masterful. The title and idea come from the Tswana proverb: “when the good doctor can’t cure you, find the less good doctor.” Very often when you’re making a work of art, you start with a good, clear idea and everything seems possible. As the work begins–the writing, the drawing, the rehearsal–all the imperfections emerge and your only hope is elements from the periphery, things you weren’t really thinking about, start to come into the centre and give shape and meaning to the first impulse. These are what I’d call the less good ideas, what follow from an imperfect good idea. They are the raw material from which art is made, which has to be made, where there is the possibility of surprise.

TLmag: Do you think the role of the artist is more to make more sense/non-sense of the world than to make commentary?

W.K.: I think so. There may be a commentary that emerges from the sense or non-sense, but the danger is to start with the commentary and then work towards the art. The hope is the work itself will not just give you an answer, but even provide the questions and make connections you hadn’t thought of before. It does this from a belief in the need we have as humans to take the clues, the fragmentary things we see and make possible sense of them.